Please review: Levine, Robert and Wolff, Ellen. Social Time: The Heartbeat of Culture. Psychology Today. 1985.

Action Item: Kohl's Values Americans Live By

Culture

How to examine it?

culture shockethnocentrismcultural relativity

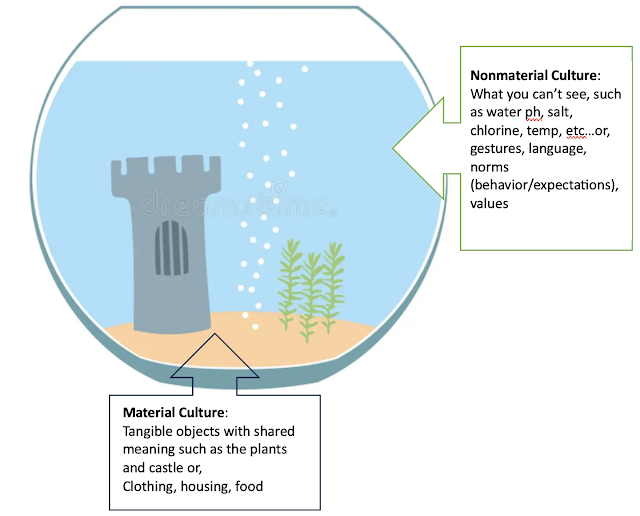

What is it made up of?

materialnonmaterial

norms

folkways

mores

taboos

language

As we learned in our last lesson, humans are born to be nurtured. We are social beings born into communities of other people. The larger communities of people who share meaning in everyday life form a culture. So as babies we are born into a culture. Because culture is so omnipresent, it surrounds us before we are even born. And so, similar to how a fish has never known what it is like to live out of water, humans have been surrounded by culture their whole lives. Thus, culture is the first force of socialization, or nurture, that we are influenced by.

In the case of the Japanese toilet, not only does it look and function differently from ours, but it also represents fundamentally different non-material culture. The Japanese are very germ conscious and they try hard not to spread germs. They also do not have a lot of furniture - they do not sit on furniture in their houses so why would they sit on a porcelain throne in a bathroom? And finally, they are used to sitting and squatting in positions difficult for westerners.

In the case of the Japanese toilet, not only does it look and function differently from ours, but it also represents fundamentally different non-material culture. The Japanese are very germ conscious and they try hard not to spread germs. They also do not have a lot of furniture - they do not sit on furniture in their houses so why would they sit on a porcelain throne in a bathroom? And finally, they are used to sitting and squatting in positions difficult for westerners.Materially: what is it?

In either case, the point is that there is nothing "natural" about culture. In other words, there are no weird ways of doing things that come quite natural to us. There are only different ways of doing things. And material culture, although physically different, often represents a different non-material culture, such as a different way of thinking about the world.

Instead of judging other cultures, sociologists seek cultural relativity or trying to understand a culture from that culture's own standards. This will help us to understand people better and be more empirical and less judgemental. Below is a graphic image called the Iceberg of Culture, originally printed in a 1984 American Foreign Service Handbook (cited by sociologist Robin DiAngelo, 2016 and digitally designed by Dr. Robert Sweetland on his website for educators.)

Cultural Universals and Human Nature

Using the article, please answer these questions:

5. How did the author conduct cross-cultural research about time in the U.S. and Brazil?

6. What did he find quantitatively and qualitatively?

7. What does the social construction of the shared meaning of being "late" reveal?

8. What other data did researchers use to study time around the world?

What are norms?

Why are norms important?

There are two important general lessons from norms:

- When interacting with other cultures, recognizing norms is important because if we fail to acknowledge these differences, we run the risk of offending someone or even a whole culture of people.

- Second, norms help us see that we have been shaped to behave a certain way; they are an illustration that we are socialized by our nurture. Norms an example of the shared meaning that we learn as we grow up.

Norms that are less important are called folkways. Folkways are not crucial to the order of society and if you were to violate a folkway people would not necessarily judge you. A folkway in the United States might be addressing adults by "Mr" or "Ms" or driving the speed limit. A folkway at a dinner party might be not putting your elbows on the table.

Mores (pronounce mor AYS) are norms important to the order of a society. If you violate them, it will cause a disruption in the social setting. It is worth noting that these mores, although very important to the society, are not necessarily laws. Similar to the ideas of time being a social construct, they are just the way that people operate and even though they are not written into laws, they are important to the function of society. The more of how to cross a street can be found in lots of videos on youtube. Watch this video of an intersection in India and think about who has the right of way? There may not be a law about it, but those drivers know what they are doing. Would an American know the more of how to cross the street? Note how the person crossing the street is aware of the norms of traffic and so the pedestrian successfully crosses without getting hit.

And a British explanation of Italian street crossing norms here.

Finally, the most serious norms are taboos. Taboos are things that you do not even want to think about because it is embarrassing to even imagine it. For example, look at this port-a-potty created by an artist in Switzerland. Would you be able to use it?

Would you be able to use a toilet if it looked like everyone could see you, even though you knew they could not? This is a taboo because even though people could not see us, the mere thought of them seeing us would make us hesitant. In other words, simply thinking about doing this is embarrassing and so we don't want to even think about it. Perhaps, that is why we have so many euphemisms for using the toilet: using the john, the restroom, the bathroom, the lavatory, the men's room, washroom, powder room?

9. Have you experienced a different set of norms from another culture either by traveling somewhere or by meeting a foreigner here in America? What was it like? Were there misunderstandings?

Something else that you might want to inquire about is another culture's norms; where you would like to travel? What are all of the norms you should know if you travel there? Find out what unique norms exist in their culture. Here is a link to cultural etiquette around the world:

Set 1. Auto, turtle, basket, birdSet 2. Laundry, beer, clothingSet 3. A chair, a spear, a couch

13. What are three words to describe this bridge:

What is the importance of language?

The importance of language was first highlighted by researchers, Saphir and Whorf. Their hypothesis and conclusion was that language shapes how people think, especially when categorizing and naming. For example, in the color samples above, Americans typically group the chips by blue and green, but Tarahumara people do not have a word for blue and green, instead they have words that mean the color of water and the color of night. Because each group of people have different words with different meanings, it shapes how they think.

Set 1. Auto, turtle, basket, birdStudents generally select auto or basket using the culturally familiar categorizing device of machines vs. non-machines or and movement vs. non-movement. At least some non-western cultural groups, however, would see birds as most different because their culture emphasizes shape and birds are relatively angular rather than rounded in shape. Our culture tends to emphasize use or functionality. Thus correctness would be culture-dependent.Set 2. Laundry, beer, clothingStudents generally, with great assurance, select beer as most different. Functionality places clothing and washing machines together. Yet, at least one culture views clothing as different because laundry and beer are both “foamy”. Visual appearance is most salient. US slang for beer (“suds”) also recognizes the attribute of foaminess.Set 3. A chair, a spear, a couchStudents again select the “wrong” answer—at least from the perspective of traditional West African cultures. US Americans tend to emphasize use, thus placing couch and chair together as types of sitting devices (i.e. “furniture”). Ashanti apparently would see the “couch” as the most different because both a chair and a spear can symbolize authority.

Evidence of different languages with genderized nouns shaping how people think about those things:

- The NY Times ran a story about how the idea of language affecting our thoughts. See that article here.

- The ASA's Society Pages shares research by sociologist Matt Wray highlighted on NPR's Code Switch. Why would using the term "white trash" support white supremacy?

- This New Yorker article explains the research of professor Adam Alter on the hidden power of words and naming.

- Also, here is a study explaining that without language, numbers do not make sense.

- This episode of On Being from NPR is about Rabbi Heschel who insightfully explained "words create worlds." Here is a link to a medium article about Heschel and words. And this link to a passage about the importance of words from Heschel to William Blake.

- David Treuer is an Ojibway translator who explains the power and importance of language on this episode of On Being.

- The episode Lost in Translation from NPR's Hidden Brain is a social science podcast from NPR and this episode explores how language shapes our thoughts.

- Also, see this post about politics and how the use of English frames every debate especially the debate over gun violence.

- Here is a list of untranslatable ideas about love from around the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment