As students enter, please look over the reading by Joel Best, "The Truth about Damned Lies and Statistics."

Be ready to answer questions about the reading.

Small group discussion of reading.

1. What's the problem with the statistic about children killed by guns?

2. According to Best, what are the 2 harmful ways that people view statistics?

3. How does Best say people should view statistics?

4. Rather than viewing a statistic's flaws, how does Best say that people should be thoughtful about statistics?

How to be critical of statistics/research:

Ask questions.

Don't just accept the data but ask where it came from.

Look for a section (usually at the end) called Discussion or Limitations; usually, authors are critical of their own work.

Apply: Best's reading to your own research.

Individually

5. What statistics or claims are in the research that you found? Apply some of Best's suggestions to statistics from your research article.

Applying Critical Thinking to Violence in Chicago

Examining Statistics in Sociology (and generally) requires critical thinking. By critical, I mean being detailed and inquisitive about the stats. For example, let's examine the following claim that we hear often (and many of us or our parents may even have said).

Claim: There is a lot of violence in Chicago.

6. How can we be critical of this claim; what questions would you ask before accepting this claim as fact? What details would you want to know?

Research this claim critically. In small groups try to examine this claim critically and then explain your finds to the class. What nuances should we know before making this claim?

Remember that statistics are rhetorical - they must be defined and explained by words.

From the way CPD has presented the numbers it’s not at all clear how many of the 1,127 arrests were actually related to last year’s 1,417 carjacking cases. Deenihan didn’t explain that oftentimes CPD arrests multiple people related to a single carjacking incident, nor did he mention how many of those arrests were for incidents that happened in prior years. In a table breaking down arrestees’ age ranges in five-year increments, the 15-20 age group was indeed the largest in 2020. More than half of the people arrested, however, were actually over the age of 20.

While carjacking had spiked, last year saw 21,567 fewer robberies, burglaries, and thefts compared to 2019. This was part of a yearslong trend in the decline of these types of crimes. About 18,000 parked, unattended cars are stolen every year in Illinois, and that hadn’t become more common in 2020; CPD claims that these days cars are easier to steal because many people leave their key fobs in their vehicles. “Meanwhile this one uptick in this one subcategory of robbery had story after story and press conference after press conference,” she remarked about carjacking.

Here are some sites to help you:

Cross-Cultural Research

Cross-sectional Research on Crime Within the United States

Violent crime is generally contrasted with property crime, with the latter defined as the taking of money or property without force (or the threat of force) against the victims. Note that in these definitions, robbery counts as violent crime whereas burglary does not. Comparing the the number of committed crimes in U.S. by category, property crime far outnumbers violent crime, while aggravated assault accounts for some two-thirds of all violent crime.

Crime overall is relatively low in Illinois and the homicide rate is middle of the pack.

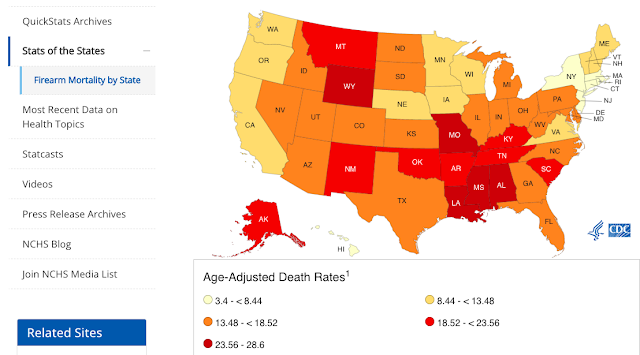

Gun deaths by state from World Population Review

Firearm deaths by state from CDC

Cross Sectional Research within Chicago

Longitudinal Data

Longitudinal Data

Crime in Chicago; What Does the Research Tell Us? from Northwestern U.

The violence was also extremely concentrated. Skogan said 50 percent of all the shootings in 2016 occurred in just a handful of neighborhoods, including Austin, Garfield Park, North and South Lawndale, Englewood, and West Pullman. The crime is even more concentrated in those communities, often occurring within just a few blocks. There is one four-by-four block area in Humboldt Park, Skogan said, that has been in the top 5 percent of shootings in the city every year for 27 years. Note that the crime rate has not spiked generally for all Chicagoans. As the graph above and the text above that explains, the crime is particularly high in smaller communities within Chicago.

The Chicago Police Department reports 661 murders occurred as of Dec. 10, 2022, down 15% from 2021 when the tally was 776. Overall shootings are also reported as down by about 20% from 2021 numbers, from 3,399 to 2,718. But reported incidents of motor vehicle theft have nearly doubled from 2021, from 9,933 to 19,238. Theft numbers also showed a steep increase.

How safe is Chicago? The answer depends on where you're standing.

The North Side is as safe as it's been in a generation, with a homicide rate that has declined steadily throughout this century, barely ticking up during the especially violent years of 2016 and 2020, then falling again in 2021, even as the city as a whole experienced its bloodiest year since the mid-1990s, according to Chicago Police Department data.

The homicide rate for the city’s four North Side police districts (the 18th, 19th, 20th and 24th) last year was 3.2 residents per 100,000, according to analysis of data from the University of Chicago Crime Lab—lower than Evanston’s, Champaign’s and Springfield’s, based on data from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Overall, Chicago’s per-capita murder rate is higher than in New York City or Los Angeles, but is lower than in Midwestern cities such as Detroit, Milwaukee and St. Louis.

Qualitative Understanding of Violent Crime

What is "violent" crime? Does armed robbery count?

The FBI categorizes violent crime as, "violent crime is composed of four offenses: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault. Violent crimes are defined in the UCR Program as those offenses that involve force or threat of force."

Cross-Cultural Comparison of Chicago to Other Big Cities

Reviewing Unit 1:

Is the data above macrosociology or microsociology? Why?

What would data look like that is the opposite?

What questions would a structural functional sociologist ask about the data above?

What questions would a sociologist ask about the data above using the conflict paradigm?

What questions would a symbolic interactionist sociologist ask about the data above?

What conclusions might you make about the data above using a sociological imagination?

How might the data above apply to the social construction of reality?