Pay Gap

One of the most widely talked about disparities is the gender pay gap. Sociologists have examined the income of females compared to males and through a number of different studies showing females are paid less (about 80%) than what males are paid. Because of this widely studied disparity, the American Sociological Association published a 2019 public policy recommendation that concluded,

a woman working fulltime, year-round in 2017 was typically paid just 80 cents for every dollar paid to a man working full-time, year-round.... Gender wage gaps persist in all 50 states and in nearly every occupation. Significant wage gaps also exist for mothers compared to fathers, LGBTQ women compared with men, and women with disabilities compared to men with disabilities.

Skeptics of the wage gap contend that it is due to differences in education levels or the kinds of jobs that women choose. But studies show that at the very beginning of a woman’s career, just one year after college graduation, women working full time were paid only 82% of what their male colleagues earned and ... that wage gaps grow over time. For women overall, even when accounting for factors like unionization status, education, occupation, industry, work experience, region, and race, 38% of the wage gap remains unexplained. Data make clear that discrimination— based on conscious and unconscious stereotypes—is a major cause of this unexplained gap. A recent experiment revealed, for example, that when presented with identical resumes, one with the name John and the other with the name Jennifer, science professors offered the male applicant for a lab manager position a salary of nearly $4,000 more, additional career mentoring, and judged him to be significantly more competent and hirable. When women lose out on earnings because of discrimination, families and the economy suffer.

The rest of the publication may be even more enlightening and the citations may be useful, but what is important is that this report shows that there is a considerable wage gap even when controlling for factors like education, type of work, and experience.

Women earn about 80% of what men earn and women earn less compared to men of similar education at every level. Using census data from 2014, this is true for all levels of income and education; from women in poverty to women with professional degrees. It is also true for women working right out of college compared to their male cohorts. It is true for single households headed by women compared with men. (Ferris and Stein)

The National Women's Law Center published this report showing that, Women who work full time, year round in the United States were paid only 82 cents for every dollar paid to their male counterparts in 2018. For many groups of women, the gaps are even larger. This document provides details about the wage gap measure that the Census Bureau and the National Women’s Law Center (NWLC) use, factors contributing to the wage gap, and how to close the gap. 4. Are women paid a similar income to men when they get out of college, but the pay gap shows up after they have kids?

The Gender Pay Gap from the Washington Post (Try this link and login with your LUC credentials) does a terrific job of explaining the dynamics and nuances that lead to unequal pay for women. (If the link doesn't work, see the graphics below but here is a copy of the article without interactive graphics) The data is from 2017 and was compiled using microdata from IPUMS USA for the pay gap by occupation, for the historical change in earnings by share of women in the job, and for the breakdown by education and by workweek. We used decennial census and American Community Survey 5-year data because is the most comprehensive, despite not being the most up to date, and used people who had worked most of the year. For the recent, general data points, we used data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. |

In the graphic above, the purple circles represent the number of females in a particular occupation and the yellow circles represent the number of males. The red line represents the pay gap.

This graphic shows that when the jobs are lined up from most female to most male, the disparity in pay is greater the more male a job is:

6. How is the pay gap different between jobs that are more female versus jobs that are more male?

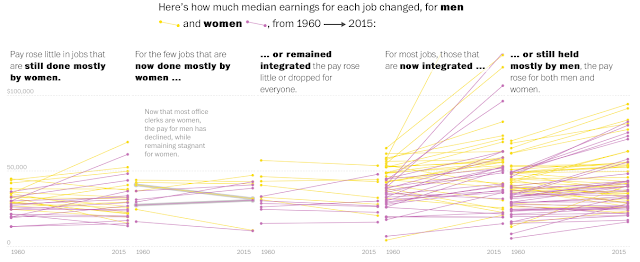

These charts show that from 1960-2015, jobs that were mostly female (far left) did not grow in income nearly as much as jobs that were mostly male (far right). And jobs that became more female (2nd to left) pay declined for men. In other words, jobs that are perceived as being female jobs are paid less. |

And the more female an industry becomes, the less money that field makes.

|

This graph addresses the idea that women work part-time so they make less than men. Note that part-time women actually make more than part-time males. However, the majority of women work full time or longer but they make less than men. |

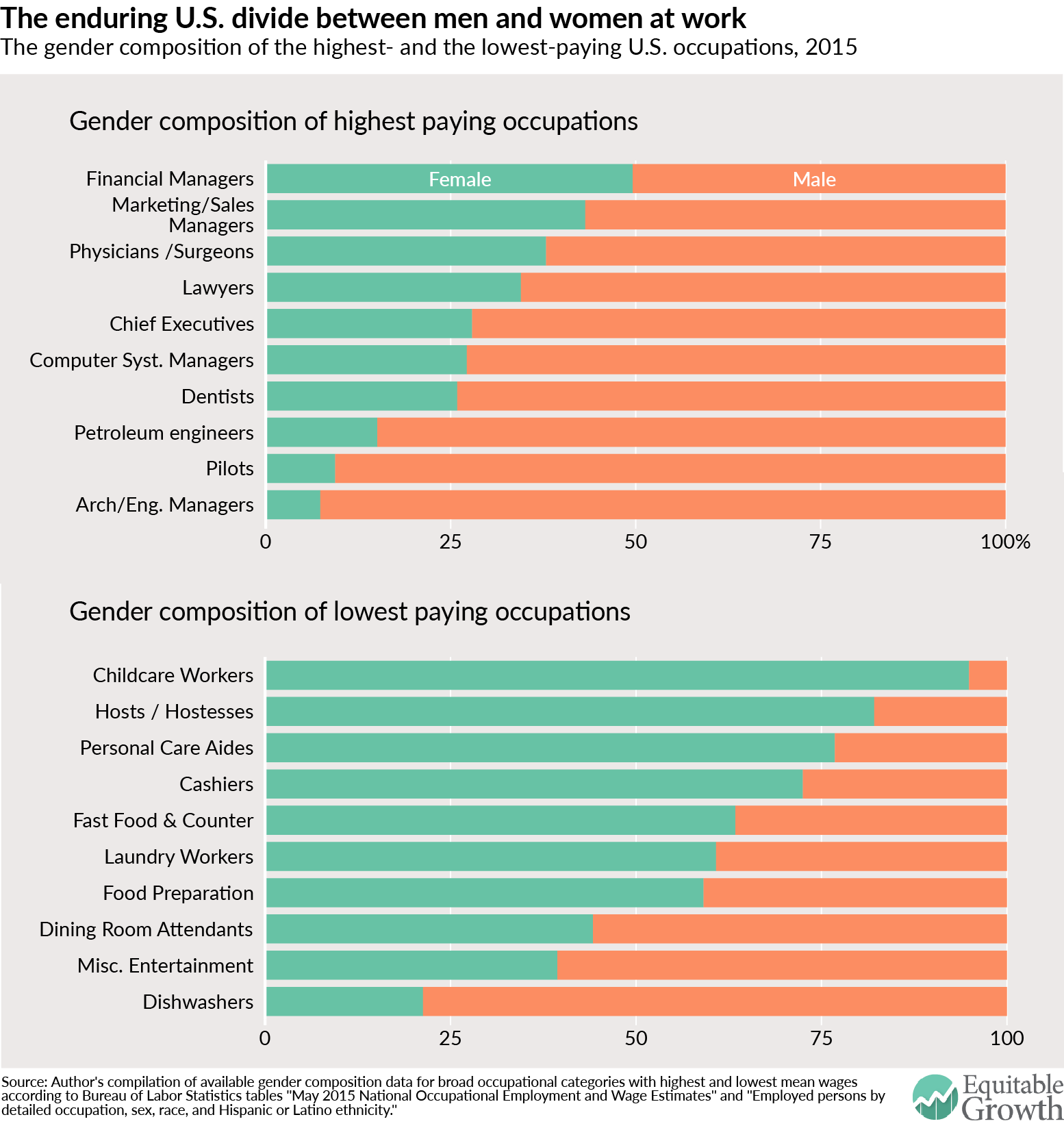

The more women that work in an industry, the lower-paid those jobs are. This link from Payscale illustrates that as does this from Payscale. Examine the following graph from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth then answer the questions.

|

This graph shows the higher paid occupations are more male and the lower-paid occupations are more female.

|

Hiring

This research from Contexts (2019) shows that employers hire applicants by gender, based on their perception of what the gender of the job should be. So, as jobs become more sewed toward one gender, there is less of a chance that employers will hire the other gender because of implicit bias in their own perception of what gender the job applicant should be. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts in the hiring process.

And, as reported in The Pushes and Pulls of Gendered Occupations (2018), "Latonya Trotter finds that it’s not just exclusion from men’s professions, but the inclusionary policies of women’s professions that maintain distinctly gendered fields." Her research finds that women who "want children, and appreciate the autonomy and flexibility," gravitate toward nursing jobs that allow them to, "work part-time and take a long time to finish their schooling [without] career penalties for taking time off, and seniority is not highly rewarded in the profession."

Structuring programs and jobs that offer flexibility will increase the number of highly qualified individuals by attracting females who want that flexibility.

Another way to be more inclusive in hiring may begin with being mindful of who gets selected for consideration in the first place. Sociologist Jill Yavorsky found that the polarization in gendered traits shows up in hiring practices, especially when overlapped with social class, published in the Journal of Social Forces here. Those in charge of hiring may select applicants based on their own biases about whether the job is masculine and manual labor or not.

Job flexibility and unpaid labor

One reason why females seek flexibility on their job is explained by this research from the Society Pages (2019) which shows women do a majority of the work at home. This includes not only physical and emotional work, but also cognitive labor too. And women have reason to worry about housework because, as NY Times Upshot (2019) found, Women, but Not Men, Are Judged for a Messy House.

[Women are] still held to a higher social standard, which explains why they’re doing so much housework.... Even in 2019, messy men are given a pass and messy women are unforgiven. Three recently published studies confirm what many women instinctively know: Housework is still considered women’s work — especially for women who are living with men.

Women do more of such work when they live with men than when they live alone, one of the studies found. Even though men spend more time on domestic tasks than men of previous generations, they’re typically not doing traditionally feminine chores like cooking and cleaning, another showed. The third study pointed to a reason: Socially, women — but not men — are judged negatively for having a messy house and undone housework.

the U.S. is the only country among 41 nations that does not mandate any paid leave for new parents, according to data compiled by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and current as of April 2018. The smallest amount of paid leave required in any of the other 40 nations is about two months.

5. Using the graphs above, out of the highest paying jobs in the U.S., which is the MOST female?

|

Inclusive promotion

Implicit bias can also affect women on the job. Harvard Business Review conducted a study that,

found almost no perceptible differences in the behavior of men and women. Women had the same number of contacts as men, they spent as much time with senior leadership, and they allocated their time similarly to men in the same role. We couldn’t see the types of projects they were working on, but we found that men and women had indistinguishable work patterns in the amount of time they spent online, in concentrated work, and in face-to-face conversation. And in performance evaluations men and women received statistically identical scores. This held true for women at each level of seniority. Yet women weren’t advancing and men were.

Their conclusion was that,

While programs aimed at strengthening women’s leadership skills are valuable, companies also need to focus on the more fundamental — and more difficult — problem of reducing bias. This means trying bias-reduction programs, but also developing policies that explicitly level the playing field. One way to do so is to make promotions and hiring more equal. Significant research suggests that mandating a diverse slate of candidates helps companies make better decisions. A study by Iris Bohnet of Harvard Kennedy School showed that thinking about candidates in groups helped managers compare individuals by performance — but when managers evaluated candidates individually, they fell back on gendered heuristics.

Salary.com has an explanation of the gender pay gap. Their explanation includes these: - Earnings Increase with Age, and the Gender Pay Gap Does, Too

- Education Does Not Combat the Gender Pay Gap

- Location Plays a Huge Role in the Gender Pay Gap

7. Does this provide evidence that there is a gap in how much income females earn compared to men? What else would you like to know or is there anything you are still dubious about?

Inequality also means different treatment for females and males on the job.

"When women speak, they shouldn’t be shrill. Clothing must flatter, but short skirts are a no-no. After all, “sexuality scrambles the mind.” Women should look healthy and fit, with a “good haircut” and “manicured nails.”

- These were just a few pieces of advice that around 30 female executives at Ernst & Young received at a training held in the accounting giant’s gleaming new office in Hoboken, New Jersey, in June 2018.

- One example of the inequality affecting the attitudes of an engineer in the tech industry is a report by Kara Swisher about the engineer's manifesto (2017).

- Harvard Business Review conducted a study that the difference in promotion rates between men and women in this company was due not to their behavior but to how they were treated. This indicates that...Gender inequality is due to bias, not differences in behavior.

Besides applicants' self-selecting jobs based on gender, employers also select based on gender. This research from Contexts (2019) shows that employers hire applicants by gender, based on their perception of what the gender of the job should be.

8. Explain what the research in the Contexts article above says about jobs and gender.

Females and unpaid labor

This research from the Society Pages (2019) shows women do a majority of the work at home. This includes not only physical and emotional work, but also cognitive labor too.

From NY Times Upshot (2019),

Women, but Not Men, Are Judged for a Messy House

They’re still held to a higher social standard, which explains why they’re doing so much housework, studies show. Even in 2019, messy men are given a pass and messy women are unforgiven. Three recently published studies confirm what many women instinctively know: Housework is still considered women’s work — especially for women who are living with men.

Women do more of such work when they live with men than when they live alone, one of the studies found. Even though men spend more time on domestic tasks than men of previous generations, they’re typically not doing traditionally feminine chores like cooking and cleaning, another showed. The third study pointed to a reason: Socially, women — but not men — are judged negatively for having a messy house and undone housework.

From the American Journal of Sociology, this 2020 research by Allison Daminger shows how difficult breaking gender inequality may be. Full article here. From the abstract:

This article extends prior research on barriers to equality by closely examining how couples negotiate contradictions between their egalitarian ideals and admittedly non-egalitarian practices. Data from 64 in-depth interviews with members of 32 different-sex, college-educated couples show that respondents distinguish between labor allocation processes and outcomes. When they understand the processes as gender-neutral, they can write off gendered outcomes as the incidental result of necessary compromises made among competing values. Respondents “de-gender” their allocation process, or decouple it from gender ideology and gendered social forces, by narrowing their temporal horizon to the present moment and deploying an adaptable understanding of constraint that obscures alternative paths. This de-gendering helps prevent spousal conflict, but it may also facilitate behavioral stasis by directing attention away from the inequalities that continue to shape domestic life.