Labor Day holiday was born out of a mixture of events closely linked to Chicago in the 1800s. Chicago was the center of American industrialism and growth during the 19th century and so, it was also ground zero for the labor movement which was fighting for workers' rights and better conditions in industrial jobs. Before it was a federal holiday, there was a parade of workers held in New York City as early as 1882. This was just one example of numerous movements to give workers more rights and respect throughout the industrial age. But that movement reached it's apex in Chicago.

From Labor Movement to Haymarket to May Day

By 1884, there was national momentum to unite and support workers. From Eric Chase writing for IWW (1993),

At its national convention in Chicago, held in 1884, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (which later became the American Federation of Labor), proclaimed that "eight hours shall constitute a legal day's labor from and after May 1, 1886."... On May 1, 1886, more than 300,000 workers in 13,000 businesses across the United States walked off their jobs in the first May Day celebration in history. In Chicago, the epicenter for the 8-hour day agitators, 40,000 went out on strike with the anarchists in the forefront of the public's eye. With their fiery speeches and revolutionary ideology of direct action, anarchists and anarchism became respected and embraced by the working people and despised by the capitalists.

The names of many - Albert Parsons, Johann Most, August Spies and Louis Lingg - became household words in Chicago and throughout the country. Parades, bands and tens of thousands of demonstrators in the streets exemplified the workers' strength and unity, yet didn't become violent as the newspapers and authorities predicted.

More and more workers continued to walk off their jobs until the numbers swelled to nearly 100,000, yet peace prevailed. It was not until two days later, May 3, 1886, that violence broke out at the McCormick Reaper Works between police and strikers.

Full of rage, a public meeting was called by some of the anarchists for the following day in Haymarket Square to discuss the police brutality. Due to bad weather and short notice, only about 3000 of the tens of thousands of people showed up from the day before. This affair included families with children and the mayor of Chicago himself. Later, the mayor would testify that the crowd remained calm and orderly and that speaker August Spies made "no suggestion... for immediate use of force or violence toward any person..."

As the speech wound down, two detectives rushed to the main body of police, reporting that a speaker was using inflammatory language, inciting the police to march on the speakers' wagon. As the police began to disperse the already thinning crowd, a bomb was thrown into the police ranks. No one knows who threw the bomb, but speculations varied from blaming any one of the anarchists, to an agent provocateur working for the police.

Enraged, the police fired into the crowd. The exact number of civilians killed or wounded was never determined, but an estimated seven or eight civilians died, and up to forty were wounded. One officer died immediately and another seven died in the following weeks. Later evidence indicated that only one of the police deaths could be attributed to the bomb and that all the other police fatalities had or could have had been due to their own indiscriminate gun fire. Aside from the bomb thrower, who was never identified, it was the police, not the anarchists, who perpetrated the violence.

Today we see tens of thousands of activists embracing the ideals of the Haymarket Martyrs and those who established May Day as an International Workers' Day. Ironically, May Day is an official holiday in 66 countries and unofficially celebrated in many more, but rarely is it recognized in this country where it began.

The labor protests led to the Haymarket Affair from Chicago Encyclopedia,

Though most labor activity was peaceful, violent confrontations with the police also occurred. A clash on May 3rd between workers and police near the McCormick Reapers Works (left) led to the call for a protest meeting at the Randolph Street Haymarket. The Haymarket (upper center) was the starting point for two parades and the scene of a May 4th protest meeting which ended in violence.

At first, the Haymarket Affair was branded a riot and both government authorities and and pro-capitalist news organizations attempted to label the protesters as communists and socialists who were dangerous anarchists. A memorial was installed at the site honoring the police:

|

| Statue honoring police at the original Haymarket Square. |

By contrast, the memorial to the laborers, who were killed by the state under dubious evidence, was erected in 1893 but relegated to a cemetery in Forest Park.

A monument commemorating the “Haymarket martyrs” was erected in Waldheim Cemetery in 1893. In 1889 a statue honoring the dead police was erected in the Haymarket. Toppled by student radicals in 1969 and 1970, it was moved to the Chicago Police Academy.

From May Day to Pullman Strike to Labor Day

Despite May Day becoming an international holiday for laborers, the association with socialism kept it's significance at bay in the U.S. It was not until more labor unrest, also in Chicago, that a national Labor Day holiday was solidified on the U.S. calendar.

From Britannica,

In 1889 an international federation of socialist groups and trade unions designated May 1 as a day in support of workers, in commemoration of the Haymarket Riot in Chicago (1886). Five years later, U.S. Pres. Grover Cleveland, uneasy with the socialist origins of Workers’ Day, signed legislation to make Labor Day—already held in some states on the first Monday of September—the official U.S. holiday in honour of workers.

And the New York Times explains that,

... it took several more years for the federal government to make it a national holiday — when it served a greater political purpose. In the summer of 1894, the Pullman strike severely disrupted rail traffic in the Midwest, and the federal government used an injunction and federal troops to break the strike.

It had started when the Pullman Palace Car Company lowered wages without lowering rents in the company town, also called Pullman. (It’s now part of Chicago.)

When angry workers complained, the owner, George Pullman, had them fired. They decided to strike, and other workers for the American Railway Union, led by the firebrand activist Eugene V. Debs, joined the action. They refused to handle Pullman cars, bringing freight and passenger traffic to a halt around Chicago. Tens of thousands of workers walked off the job, wildcat strikes broke out, and angry crowds were met with live fire from the authorities.

During the crisis, President Grover Cleveland signed a bill into law on June 28, 1894, declaring Labor Day a national holiday. Some historians say he was afraid of losing the support of working-class voters.

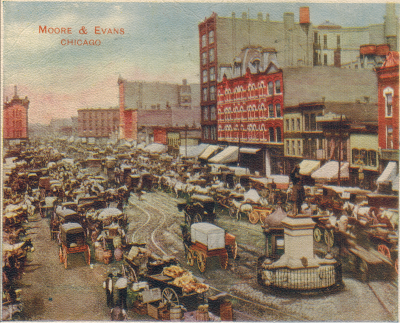

Labor Day parade in Pullman, Chicago in 1901:

And that is how Labor Day became a national holiday on the shoulders of Chicago's laborers. Meanwhile, May Day is still an international holiday celebrated in dozens of countries around the world.

Although the "market" was displaced by the expressway system, Chicago erected a monument to the Haymarket events:

Midwest Socialist Walking Tours

No comments:

Post a Comment