1. Before we begin, do you think there is a difference between how much income women earn on average compared to men?

2. If you said yes to #1, what do you think the reasons are for this difference in pay?

If you said no to #1, why not? What have you heard/read about women's incomes compared to men's?

ANSWER THE ABOVE BEFORE CONTINUING

The National Women's Law Center published this report showing that,

This editorial from Forbes critiques the idea that women are paid less for the same work as men in the same position, but even this editorial admits that,

Inequality also means different treatment for females and males on the job.

9. How did this lesson affect your understanding of the effect of gender on income and work? What specifically stood out to you?

Women are paid less

Sociologists have examined the income of females compared to males and through a number of different comparisons, the females are paid less (about 80%) than what males are paid.

This public policy recommendation published by the American Sociological Association (2019) shows that

In the last four decades, women’s educational levels and work experiences have increased dramatically. Women are over half of college graduates and nearly half the workforce, and families rely on women’s earnings. However, women are still paid less than men. More than half a century after the passage of the Equal Pay Act (EPA), a woman working fulltime, year-round in 2017 was typically paid just 80 cents for every dollar paid to a man working full-time, year-round. The gender wage gap varies by race and is larger for most groups of women of color: nationally, Black women, Native women, and Latinas working full-time, year-round were typically paid just 61 cents, 58 cents, and 53 cents, respectively, for every dollar paid to their non-Hispanic White male counterparts, while non-Hispanic White women were paid 77 cents for every dollar paid to non-Hispanic White men. Asian women working full-time, year-round were typically paid 85 cents on White non-Hispanic men’s dollar, but the wage gap is substantially larger for some communities of Asian women. Gender wage gaps persist in all 50 states and in nearly every occupation. Significant wage gaps also exist for mothers compared to fathers, LGBTQ women compared with men, and women with disabilities compared to men with disabilities.

Skeptics of the wage gap contend that it is due to differences in education levels or the kinds of jobs that women choose. But studies show that at the very beginning of a woman’s career, just one year after college graduation, women working full time were paid only 82% of what their male colleagues earned and we know that wage gaps grow over time. For women overall, even when accounting for factors like unionization status, education, occupation, industry, work experience, region, and race, 38% of the wage gap remains unexplained. Data make clear that discrimination— based on conscious and unconscious stereotypes—is a major cause of this unexplained gap. A recent experiment revealed, for example, that when presented with identical resumes, one with the name John and the other with the name Jennifer, science professors offered the male applicant for a lab manager position a salary of nearly $4,000 more, additional career mentoring, and judged him to be significantly more competent and hirable. When women lose out on earnings because of discrimination, families and the economy suffer.

3. After reading the above excerpt, are women paid less because they typically have less education than men?

The rest of the publication is available here and the citations are here.

Women earn about 80% of what men earn and women earn less compared to men of similar education at every level. Using census data from 2014, this is true for all levels of income and education; from women in poverty to women with professional degrees. It is also true for women working right out of college compared to their male cohorts. It is true for single households headed by women compared with men. (Ferris and Stein)

Women who work full time, year round in the United States were paid only 82 cents for every dollar paid to their male counterparts in 2018. For many groups of women, the gaps are even larger. This document provides details about the wage gap measure that the Census Bureau and the National Women’s Law Center (NWLC) use, factors contributing to the wage gap, and how to close the gap.

4. Are women paid a similar income to men when they get out of college, but the pay gap shows up after they have kids?

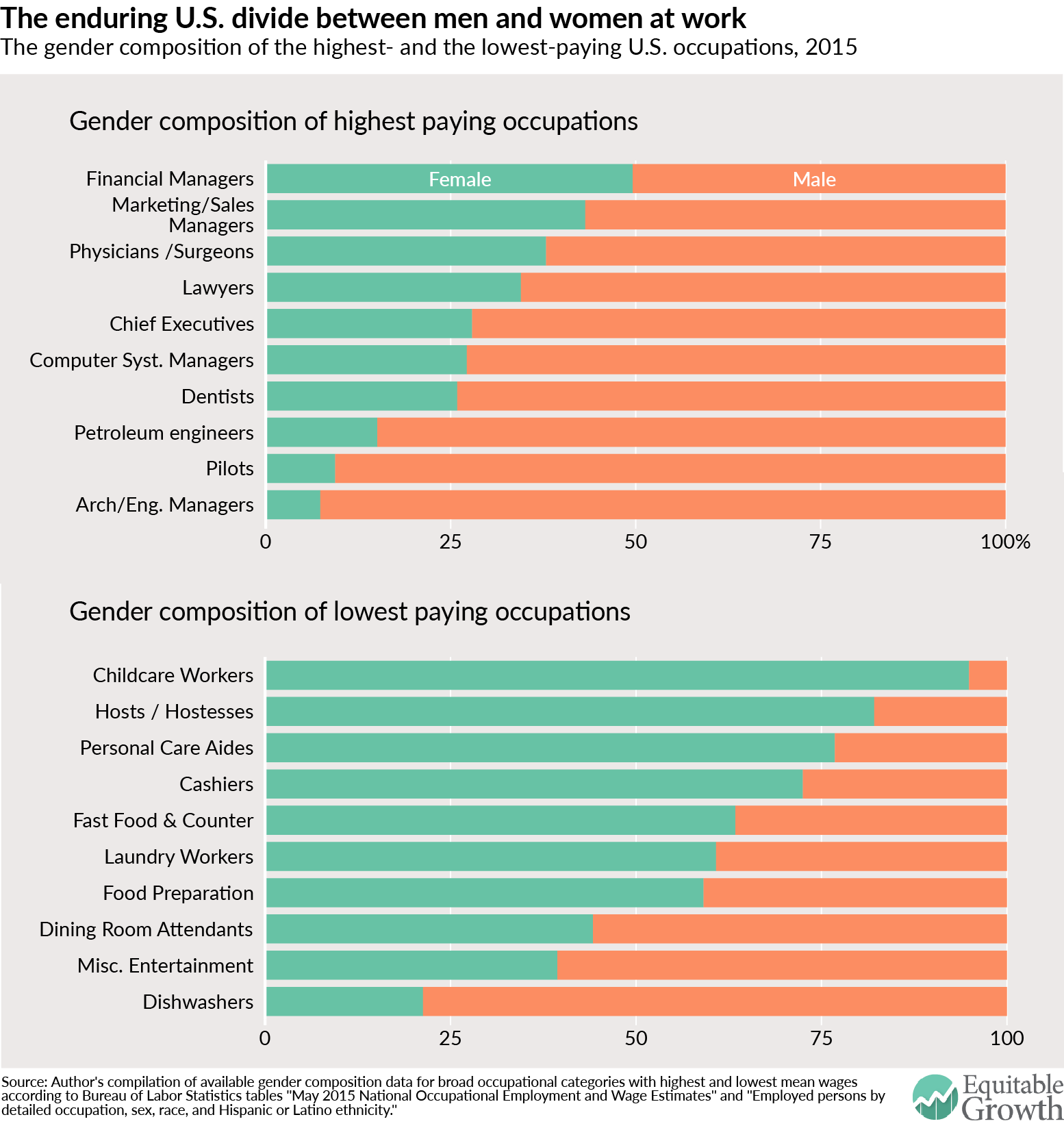

The more women that work in an industry, the lower-paid those jobs are. This link from Payscale illustrates that as does this from Payscale. Examine the following graph from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth then answer the questions.

This graph shows the higher paid occupations are more male and the lower-paid occupations are more female.

5. Using the graphs above, out of the highest paying jobs in the U.S., which is the MOST female?

The Gender Pay Gap from the Washington Post does a terrific job of explaining the dynamics and nuances that lead to unequal pay for women. (If the link doesn't work, see the graphics below) The data is from 2017 and was compiled using microdata from IPUMS USA for the pay gap by occupation, for the historical change in earnings by share of women in the job, and for the breakdown by education and by workweek. We used decennial census and American Community Survey 5-year data because is the most comprehensive, despite not being the most up to date, and used people who had worked most of the year. For the recent, general data points, we used data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

|

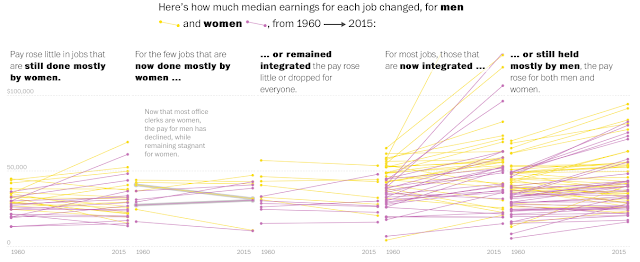

In the graphic above, the purple circles represent the number of females in a particular occupation and the yellow circles represent the number of males. The red line represents the pay gap.

6. How is the pay gap different between jobs that are more female versus jobs that are more male?

These charts show that from 1960-2015, jobs that were mostly female (far left) did not grow in income nearly as much as jobs that were mostly male (far right). And jobs that became more female (2nd to left) pay declined for men. In other words, jobs that are perceived as being female jobs are paid less. |

And the more female an industry becomes, the less money that field makes.

This graph addresses the idea that women work part-time so they make less than men. Note that part-time women actually make more than part-time males. However, the majority of women work full time or longer but they make less than men.

|

This editorial from Forbes critiques the idea that women are paid less for the same work as men in the same position, but even this editorial admits that,

Of course, none of this closes the discussion on sexism. It is important to ask, for example, why women might not be as ambitious in asking for higher salaries or larger grants and why they gravitate to, say, pediatrics over orthopedic surgery. It is possible that gender discrimination significantly contributes to all this.For more info, see the Introduction to Sociology textbook (2019) from Open Stax, chapter 12.2:

Evidence of gender stratification is especially keen within the economic realm. Despite making up nearly half (49.8 percent) of payroll employment, men vastly outnumber women in authoritative, powerful, and, therefore, high-earning jobs (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Even when a woman’s employment status is equal to a man’s, she will generally make only 77 cents for every dollar made by her male counterpart (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Women in the paid labor force also still do the majority of the unpaid work at home. On an average day, 84 percent of women (compared to 67 percent of men) spend time doing household management activities (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). This double duty keeps working women in a subordinate role in the family structure (Hochschild and Machung 1989).

Salary.com has an explanation of the gender pay gap. Their explanation includes these:

- Earnings Increase with Age, and the Gender Pay Gap Does, Too

- Education Does Not Combat the Gender Pay Gap

- Location Plays a Huge Role in the Gender Pay Gap

Inequality also means different treatment for females and males on the job.

- Here is a report about the efforts to change women at Ernst and Young (2018).

"When women speak, they shouldn’t be shrill. Clothing must flatter, but short skirts are a no-no. After all, “sexuality scrambles the mind.” Women should look healthy and fit, with a “good haircut” and “manicured nails.”

- These were just a few pieces of advice that around 30 female executives at Ernst & Young received at a training held in the accounting giant’s gleaming new office in Hoboken, New Jersey, in June 2018.

- One example of the inequality affecting the attitudes of an engineer in the tech industry is a report by Kara Swisher about the engineer's manifesto (2017).

- Harvard Business Review conducted a study that the difference in promotion rates between men and women in this company was due not to their behavior but to how they were treated. This indicates that...Gender inequality is due to bias, not differences in behavior.

Besides applicants' self-selecting jobs based on gender, employers also select based on gender. This research from Contexts (2019) shows that employers hire applicants by gender, based on their perception of what the gender of the job should be.

8. Explain what the research in the Contexts article above says about jobs and gender.

8. Explain what the research in the Contexts article above says about jobs and gender.

Females and unpaid labor

This research from the Society Pages (2019) shows women do a majority of the work at home. This includes not only physical and emotional work, but also cognitive labor too.

From NY Times Upshot (2019),

Women, but Not Men, Are Judged for a Messy House

They’re still held to a higher social standard, which explains why they’re doing so much housework, studies show. Even in 2019, messy men are given a pass and messy women are unforgiven. Three recently published studies confirm what many women instinctively know: Housework is still considered women’s work — especially for women who are living with men.

Women do more of such work when they live with men than when they live alone, one of the studies found. Even though men spend more time on domestic tasks than men of previous generations, they’re typically not doing traditionally feminine chores like cooking and cleaning, another showed. The third study pointed to a reason: Socially, women — but not men — are judged negatively for having a messy house and undone housework.

From the PEW Research Center, (2019) Among 41 countries, only U.S. lacks paid parental leave,

the U.S. is the only country among 41 nations that does not mandate any paid leave for new parents, according to data compiled by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and current as of April 2018. The smallest amount of paid leave required in any of the other 40 nations is about two months.

From the American Journal of Sociology, this 2020 research by Allison Daminger shows how difficult breaking gender inequality may be. Full article here. From the abstract:

This article extends prior research on barriers to equality by closely examining how couples negotiate contradictions between their egalitarian ideals and admittedly non-egalitarian practices. Data from 64 in-depth interviews with members of 32 different-sex, college-educated couples show that respondents distinguish between labor allocation processes and outcomes. When they understand the processes as gender-neutral, they can write off gendered outcomes as the incidental result of necessary compromises made among competing values. Respondents “de-gender” their allocation process, or decouple it from gender ideology and gendered social forces, by narrowing their temporal horizon to the present moment and deploying an adaptable understanding of constraint that obscures alternative paths. This de-gendering helps prevent spousal conflict, but it may also facilitate behavioral stasis by directing attention away from the inequalities that continue to shape domestic life.

No comments:

Post a Comment